Financial Black Hole: Stablecoins Are Devouring Banks

Stablecoins are absorbing liquidity in the style of “narrow banks,” quietly reshaping the global financial architecture.

Original Title: Stablecoins, Narrow Banking, and the Liquidity Blackhole

Original Author: @0x_Arcana

Translated by: Peggy, BlockBeats

Editor's Note: As the global financial system gradually digitizes, stablecoins are quietly becoming a force that cannot be ignored. They do not belong to banks, money market funds, or traditional payment systems, yet they are reshaping the flow of the US dollar, challenging the transmission mechanism of monetary policy, and sparking a profound discussion about the "financial order."

This article starts from the historical evolution of "narrow banking," delving into how stablecoins replicate this model on-chain and, through the "liquidity blackhole effect," impact the US Treasury market and global financial liquidity. Against a backdrop of unclear regulatory policies, the non-cyclical expansion, systemic risks, and macro impacts of stablecoins have become new topics in finance that cannot be ignored.

The following is the original text:

Stablecoins Revive "Narrow Banking"

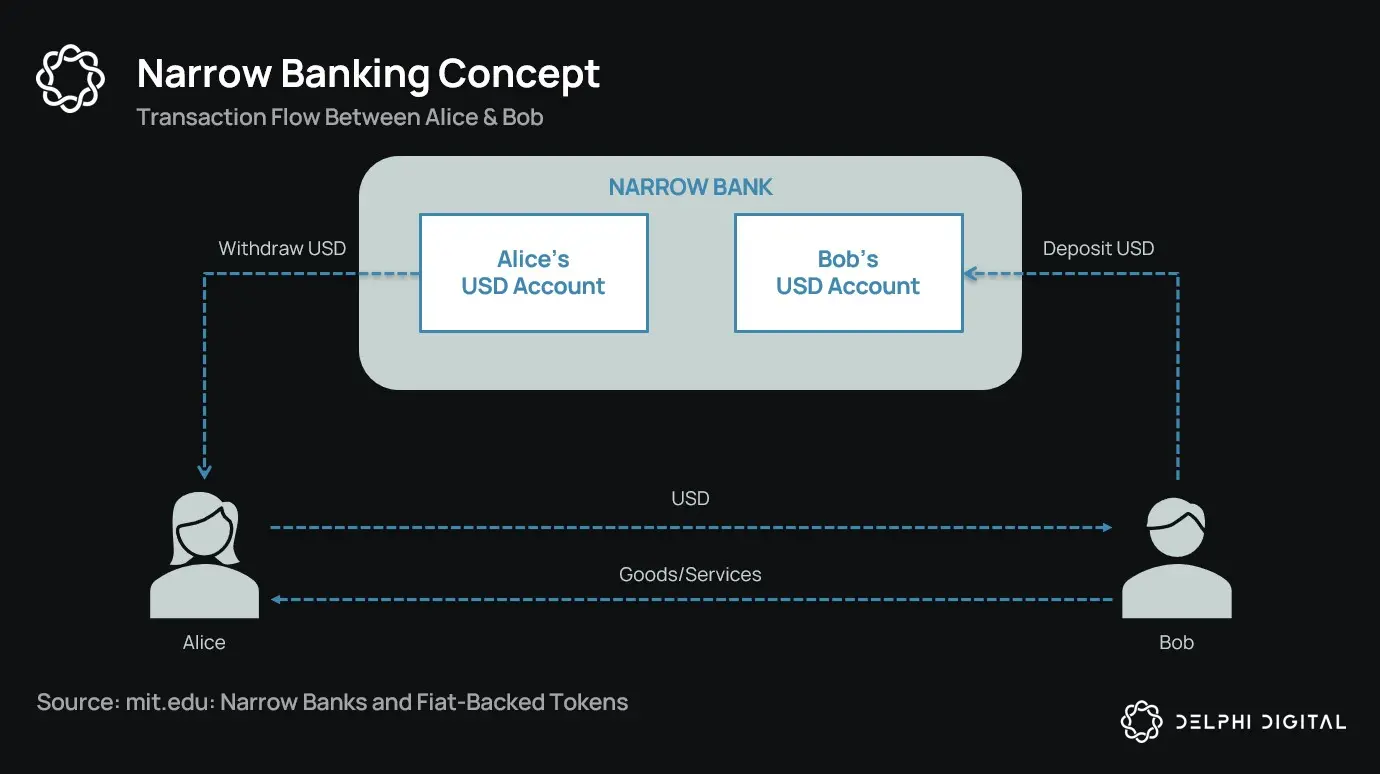

For over a century, monetary reformers have repeatedly proposed various concepts of "narrow banking": financial institutions that issue money but do not provide credit. From the Chicago Plan of the 1930s to the modern The Narrow Bank (TNB) proposal, the core idea is to prevent bank runs and systemic risk by requiring money issuers to hold only safe, highly liquid assets (such as government bonds).

But regulators have always refused to allow narrow banks to materialize.

Why? Because, while theoretically safe, narrow banks disrupt the core of the modern banking system—the credit creation mechanism. They siphon deposits from commercial banks, hoard risk-free collateral, and break the link between short-term liabilities and productive lending.

Ironically, the crypto industry has now "revived" the narrow banking model in the form of fiat-backed stablecoins. The behavior of stablecoins is almost identical to the liabilities of narrow banks: they are fully collateralized, instantly redeemable, and primarily backed by US Treasuries.

After a wave of bank failures during the Great Depression, economists from the Chicago School proposed a vision: to completely separate money creation from credit risk. According to the 1933 "Chicago Plan," banks would be required to hold 100% reserves against demand deposits, and loans could only be made from time deposits or equity, not from funds used for payments.

The original intention was to eliminate bank runs and reduce financial system instability. If banks cannot lend out deposits, they will not collapse due to liquidity mismatches.

In recent years, this idea has re-emerged in the form of "narrow banking." Narrow banks accept deposits but invest only in safe, short-term government securities, such as Treasury bills or Federal Reserve reserves. A recent example is The Narrow Bank (TNB), which applied in 2018 to access the Federal Reserve's Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER) but was rejected. The Fed worried that TNB would become a risk-free, high-yield deposit alternative, thereby "undermining the transmission mechanism of monetary policy."

What regulators are truly concerned about is: if narrow banks succeed, they could weaken the commercial banking system by drawing deposits away from traditional banks and hoarding safe collateral. Essentially, narrow banks create money-like instruments but do not support the credit intermediation function.

My personal "conspiracy theory" is: the modern banking system is essentially a leveraged illusion, operating on the premise that no one tries to "find an exit." Narrow banks threaten this model. But on closer inspection, it's not so much a conspiracy—it simply reveals the fragility of the existing system.

Central banks do not print money directly but regulate it indirectly through commercial banks: encouraging or restricting lending, providing support during crises, and maintaining sovereign debt liquidity by injecting reserves. In exchange, commercial banks receive zero-cost liquidity, regulatory leniency, and implicit bailout promises during crises. In this structure, traditional commercial banks are not neutral market participants but tools of state economic intervention.

Now, imagine a bank saying: "We don't want leverage; we just want to provide users with safe money backed 1:1 by Treasuries or Fed reserves." This would render the existing fractional reserve banking model obsolete and directly threaten the current system.

The Fed's rejection of TNB's master account application is a manifestation of this threat. The problem is not that TNB would fail, but that it might actually succeed. If people could access a currency that is always liquid, risk-free, and earns interest, why would they deposit money in traditional banks?

This is precisely where stablecoins come in.

Fiat-backed stablecoins almost perfectly replicate the narrow banking model: issuing digital liabilities redeemable for dollars, backed 1:1 by safe, liquid off-chain reserves. Like narrow banks, stablecoin issuers do not use reserve funds for lending. While issuers like Tether currently do not pay interest to users, that is beyond the scope of this article. Here, we focus on the role of stablecoins in the modern monetary structure.

The assets are risk-free, the liabilities are instantly redeemable, and they have the characteristics of face-value currency; there is no credit creation, no maturity mismatch, and no leverage.

And although narrow banks were "strangled" by regulators at the outset, stablecoins have not faced similar restrictions. Many stablecoin issuers operate outside the traditional banking system, and demand for stablecoins continues to grow, especially in high-inflation countries and emerging markets—regions that often lack access to US dollar banking services.

From this perspective, stablecoins have evolved into a "digitally native Eurodollar," circulating outside the US banking system.

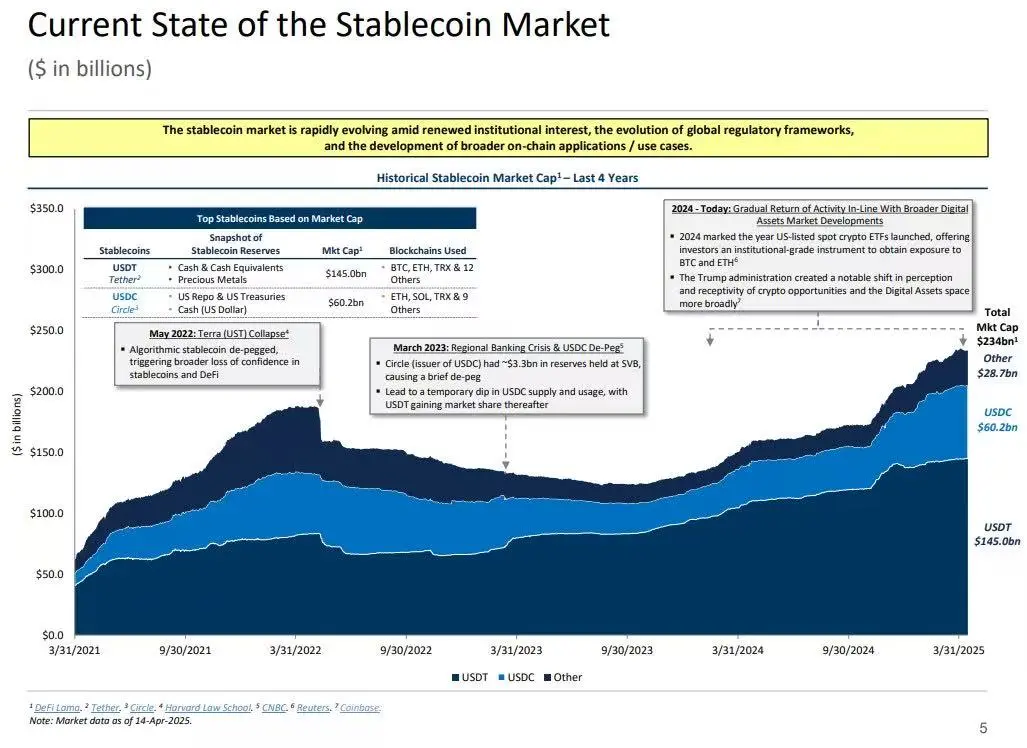

But this also raises a key question: When stablecoins absorb enough US Treasuries, what impact will this have on systemic liquidity?

Liquidity Blackhole Thesis

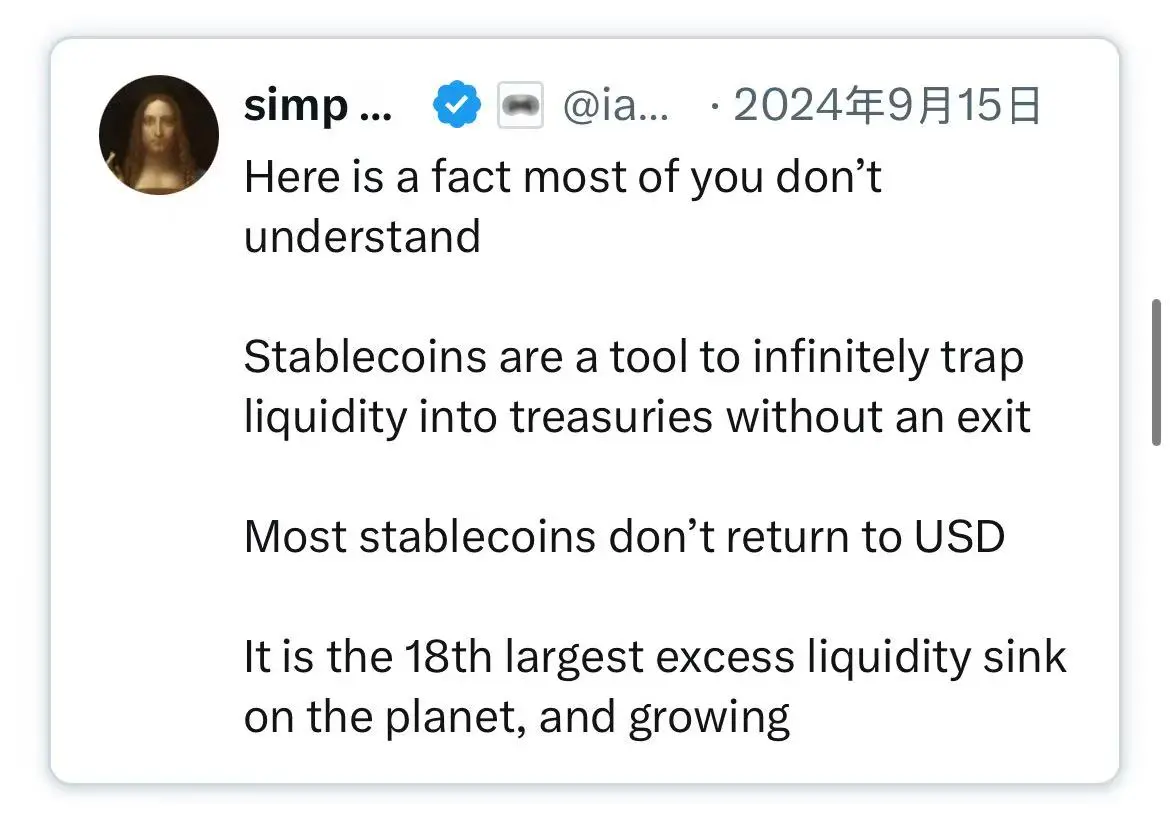

As stablecoins grow in scale, they increasingly resemble global liquidity "islands": absorbing dollar inflows while locking safe collateral in a closed loop that cannot re-enter the traditional financial cycle.

This could lead to a "liquidity blackhole" in the US Treasury market—where large amounts of Treasuries are absorbed by the stablecoin system but cannot circulate in the traditional interbank market, thereby affecting the overall liquidity supply of the financial system.

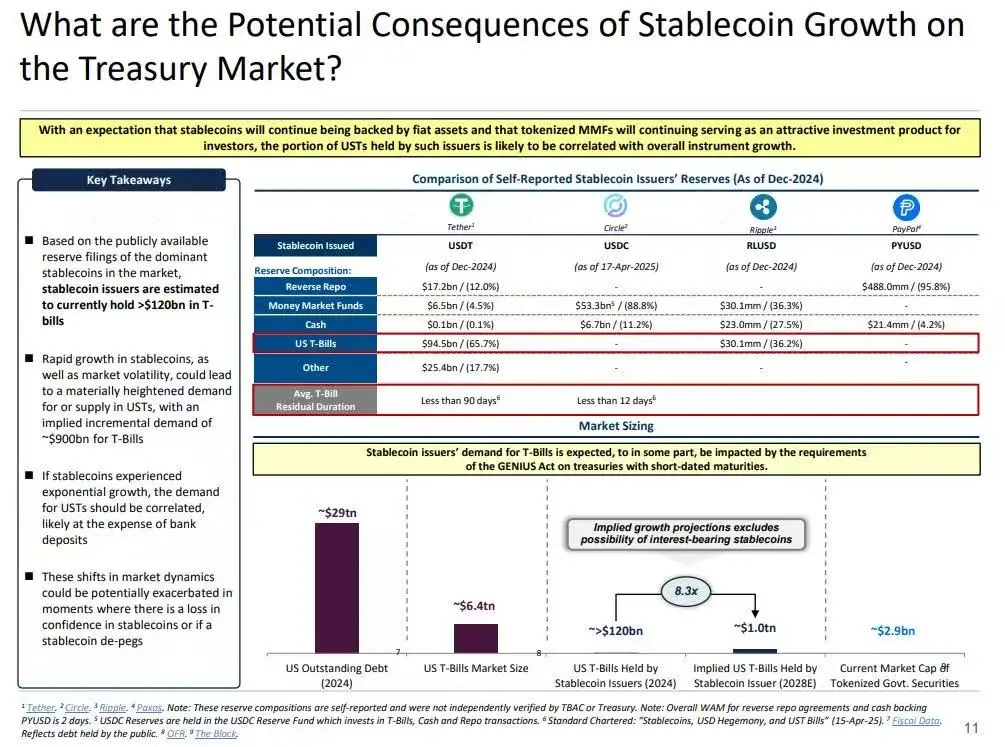

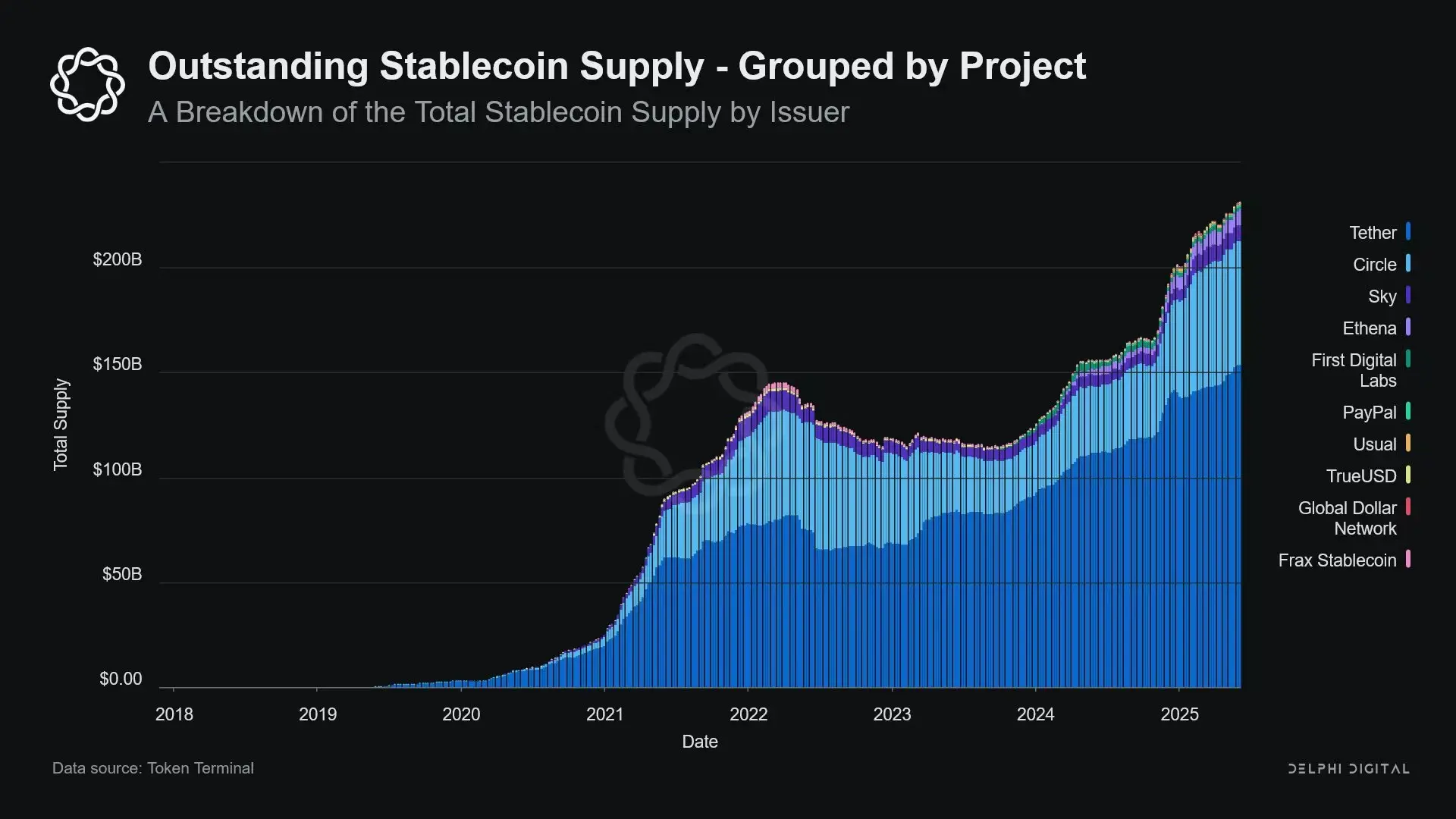

Stablecoin issuers are long-term net buyers of short-term US Treasuries. For every dollar of stablecoin issued, there must be an equivalent asset on the balance sheet—usually Treasury bills or reverse repo positions. But unlike traditional banks, stablecoin issuers do not sell these Treasuries for lending or shift into risk assets.

As long as stablecoins remain in circulation, their reserves must be continuously held. Redemption only occurs when users exit the stablecoin system, which is very rare, as on-chain users typically just swap between different tokens or use stablecoins as long-term cash equivalents.

This makes stablecoin issuers one-way liquidity "blackholes": they absorb Treasuries but rarely release them. When these Treasuries are locked in custodial reserve accounts, they exit the traditional collateral cycle—they cannot be re-hypothecated or used in the repo market, effectively being removed from the monetary circulation system.

This creates a "sterilization effect." Just as the Fed's quantitative tightening (QT) tightens liquidity by removing high-quality collateral, stablecoins are doing the same—but without any policy coordination or macroeconomic objectives.

Even more potentially disruptive is the concept of "shadow quantitative tightening" (Shadow QT) and a persistent feedback loop. It is non-cyclical, does not adjust according to macroeconomic conditions, and expands as stablecoin demand grows. Moreover, since many stablecoin reserves are held offshore in jurisdictions with low transparency outside the US, regulatory visibility and coordination become even more difficult.

Worse still, this mechanism can become pro-cyclical in certain situations. When market risk aversion rises, demand for on-chain dollars often increases, driving up stablecoin issuance and further pulling more US Treasuries out of the market—precisely when the market needs liquidity most, the blackhole effect intensifies.

Although stablecoins are still much smaller in scale compared to the Fed's quantitative tightening (QT), their mechanism is highly similar, and their macro impact is almost identical: fewer Treasuries circulate in the market; liquidity tightens; and interest rates face marginal upward pressure.

Moreover, this growth trend has not slowed down; on the contrary, it has accelerated significantly in recent years.

Policy Tensions and Systemic Risk

Stablecoins occupy a unique intersection: they are neither banks, nor money market funds, nor traditional payment service providers. This identity ambiguity creates structural tension for policymakers: too small to be regulated as a systemic risk; too important to be simply banned; too useful, yet too dangerous to be allowed to develop freely without regulation.

A key function of traditional banks is to transmit monetary policy to the real economy. When the Fed raises rates, bank credit tightens, deposit rates adjust, and lending conditions change. But stablecoin issuers do not lend, so they cannot transmit interest rate changes to the broader credit market. Instead, they absorb high-yield US Treasuries, do not offer credit or investment products, and many stablecoins do not even pay interest to holders.

The Fed's refusal to grant The Narrow Bank (TNB) access to a master account was not out of concern for credit risk, but out of fear of financial disintermediation. The Fed worries that if a risk-free bank offers interest-bearing accounts backed by reserves, it will attract massive funds out of commercial banks, potentially undermining the banking system, squeezing credit space, and concentrating monetary power in a "liquidity sterilization vault."

The systemic risk brought by stablecoins is similar—but this time, they don't even need the Fed's approval.

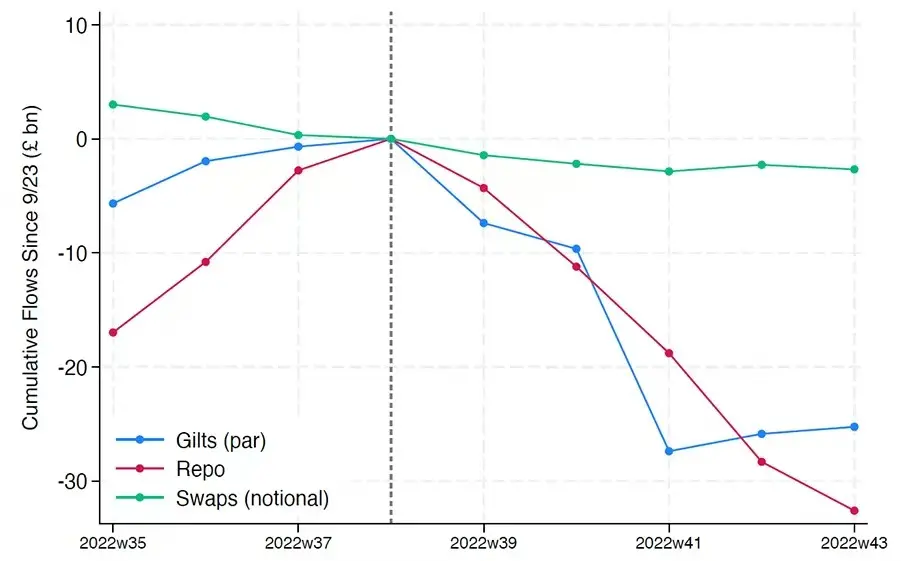

Moreover, financial disintermediation is not the only risk. Even if stablecoins do not offer yields, there is still "redemption risk": if the market loses confidence in the quality of reserves or regulatory stance, it could trigger a wave of mass redemptions. In such cases, issuers may be forced to sell Treasuries under market pressure, similar to the 2008 money market fund crisis or the 2022 UK LDI crisis.

Unlike banks, stablecoin issuers do not have a "lender of last resort." Their shadow banking nature means they can quickly grow into systemic players, but can also collapse just as rapidly.

However, just like bitcoin, there is also a small portion of "lost seed phrase" situations. In the context of stablecoins, this means some funds will be permanently locked in US Treasuries, unrecoverable, effectively becoming a liquidity blackhole.

Stablecoin issuance was initially just a marginal financial product in crypto trading venues, but has now become a major channel for dollar liquidity, spanning exchanges, DeFi protocols, and even extending to cross-border remittances and global commercial payments. Stablecoins are no longer marginal infrastructure—they are gradually becoming the underlying architecture for dollar transactions outside the banking system.

Their growth is "sterilizing" collateral, locking safe assets into cold storage reserves. This is a form of balance sheet contraction occurring outside central bank control—a kind of "ambient quantitative tightening" (ambient QT).

And while policymakers and the traditional banking system are still striving to maintain the old order, stablecoins have quietly begun to reshape it.

Recommended Reading:

Bloomberg Special Report: Binance’s Rival—A Deep Dive into How Hyperliquid Successfully Captured Market Share

Epic Crash! BTC Barely Holds the $100,000 Mark—Why Did the Altcoin Market Suffer a Bloodbath?

The Other Side of Binance Memecoin Frenzy: 1.4% Graduation Rate, Whale Losses Exceed $3.5 Million

Disclaimer: The content of this article solely reflects the author's opinion and does not represent the platform in any capacity. This article is not intended to serve as a reference for making investment decisions.

You may also like

PEPE Price Chart Signals Oversold Zone Reversal as RSI Turns Upward

Ethena (ENA) Nears Crucial $0.54 Zone After Strong 10.5% Weekly Rebound

Solana Maintains 3-Year Support, Eyes $280 Resistance for Next Key Breakout

Dogecoin Holds Above $0.20 While zVWAP Bands Define Next Key Reaction Zone